Health & Veritas: The Better Angels of Our Nature (Ep. 53)

TRANSCRIPT

Harlan Krumholz: Welcome to Health & Veritas, I’m Harlan Krumholz.

Howard Forman: And I’m Howie Forman. We are physicians and professors at Yale University. We’re trying to get closer to the truth about health and healthcare. This week we will be speaking with Professor Nicholas Christakis. But, first, what has got your recent attention, Harlan?

Harlan Krumholz: I want to just take a minute to reflect on a teacher of mine, my first chief of cardiology, the person who hired me at Yale, Barry Zaret, who passed away suddenly and unexpectedly this last week. He was in a car accident and it’s something that has really, I would say, shaken those for whom he was so important. He was a person who came to Yale in ’73, at really a relatively young age, and became chief of cardiology just a few years later at age 37. And was in that position to the point where he was one of the longest-serving chiefs of cardiology in the United States. And he’s a pioneer nuclear cardiology.

But what he’s most remembered for, I think, among many of us, is just his remarkable energy, ideas, and really his focus on relationships. And he taught us all about the importance in leadership of really not just talking about what you want to accomplish or just focusing on the particular objectives ahead but actually getting to know the people around you. And to try to inspire people in ways that appreciate what their aspirations are and what their lives are like.

He was someone in every meeting you would go in would not only talk about whatever the topic was, but would take a few minutes to connect with you as an individual and to get to learn about you. He was beloved, and he brought the section from, gosh, this is the beginning of cardiology. At the time he took over, maybe there were 10 or 12 faculty members in cardiology. There are hundreds now. It was an immense growth phase of the section.

But he was also someone who was constantly reflecting on his own family, which we’ll talk to Nicholas about the effect of people around you. And when your chief is talking a lot about things, not just the work but the life, then it kind of gave everyone else freedom to be able to talk about that and to think about their lives as well.

He was an artist and a poet, someone who was really multidimensional, and talked about all of those things too. So anyway, he was really an influential person for me. Someone who I had deep respect for and affection and love, I’ll say, and for many people in the section. So I just want to take a minute. One of the real giants of Yale. At the funeral, it was said he was 82 years old when he died, and people said, “And he’d only lived half his life.” And I think that the sense of that was that he was just so alive. He was just so engaged in so many things. He would sit in the front row—still—of Grand Rounds and ask some of the first questions of every speaker, and they would be salient questions, insightful questions. And anyway, it was just a moment for all of us, and I wanted to take just a moment on the podcast to reflect on him and to share a little bit of my memories of him, anyway.

Howard Forman: I really appreciate that, Harlan. I knew him as a colleague. He was in my department when I first came here as well, but I certainly didn’t know him as well as you. But he never ceased to stop me in the hallway, and ask me about me. And we would always chat. And I felt like he was a friend, even though we were in different departments for most of my career at Yale. So he’s a deep loss. The outpouring of affection on Twitter and elsewhere is great. And he was a life well lived.

Harlan Krumholz: One of those larger-than-life individuals who really was walk the walk, talk the talk, did everything that you would think, and showed immense integrity in every aspect of his life. Let’s get on. We’ve got Nicholas Christakis here. I mean, this is a tremendous episode for us, and so great to have Nicholas. So Howie, take it away.

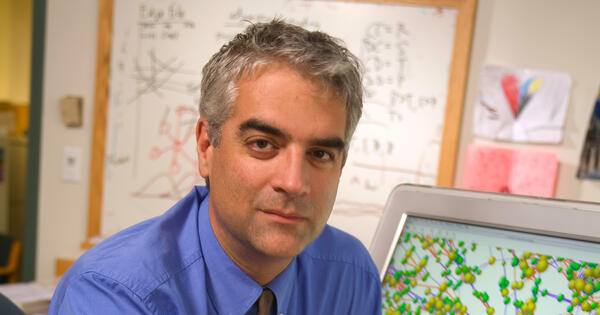

Howard Forman: Professor Nicholas Christakis is the Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science, Internal Medicine, and Biomedical Sciences at Yale University. For our listeners, a Sterling Professor is the highest academic title awarded at Yale. It is a higher attribution than even a university professor, a seemingly similar title often used at other universities. He directs the Human Nature Lab, which focuses on the human nature of our interactions with each other, combining the natural, social, and computational sciences. He’s also the co-director of the Yale Institute for Network Science, which seeks to produce and disseminate knowledge related to network science.

Professor Christakis is the author of several bestselling, well-received books, including Connected, Blueprint, and Apollo’s Arrow. And by the way, he wrote and published Apollo’s Arrow about the pandemic and its aftermath before the first year of the pandemic had even elapsed. He’s an elected member of the Institute of Medicine, a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He received his bachelor’s degree from Yale, his medical and public health degrees from Harvard, and a doctorate in sociology from the University of Pennsylvania, which is when I first met him.

There are physicians who write books. There are physicians who do great research. There are physicians who have become public intellectuals. And there are physicians who just lead and manage exceptionally well. Sometimes they might even do two of these things, but Professor Christakis has managed to do that and more. So, first, welcome to the Health & Veritas podcast. I have a lot of questions, but I am struck by how optimistic you can be about human nature, even in the seemingly darkest of times. Can you tell us what has informed that view?

Nicholas Christakis: Well, first of all, thank you for that really too-kind introduction, and both Howie and Harlan are old friends, each of you I have met in different ways. So I’m delighted to see your faces, even though the other listeners can’t see our faces, and talk to you. I think in response to your question, Howie, I would say I’m certainly characterologically optimistic. I like to think of myself as an optimistic person, and part of that is animated by the sentiment that, who wants to live a life that’s filled with pessimism and negativity? I mean, I would rather go through life being hopeful and optimistic than with my one life do the alternative.

Now, I am optimistic about human beings. I’m optimistic and I have a optimistic attitude towards what we as a population and as citizens can do to make the world better. And so let me just tell you briefly the scientific aspect of that, which is that I think it’s very common for people on the street to focus on the dark side of human nature.

And of course, we are capable of awful things, we humans are. But I think the bright side has been denied the attention it deserves, because equally we are capable of love and kindness and friendship and teaching and all these other wonderful qualities. And in fact, I would argue that these wonderful qualities must have, light must have been more powerful than darkness. I would argue that these good qualities must necessarily have been more powerful than the bad qualities. Otherwise, we would not live as a collectivity.

In other words, if every time I came near you, you were violent towards me or you stole from me or you filled me with lies, I would be better off living atomistically. We would be a species that did not live socially. So it must be the case, and indeed, it is the case, that the benefits of a connected life outweigh the costs. That we derive more benefits from being in love with each other and befriending each other and working together to achieve objectives and teaching and learning from each other. These are all magnificent things that we do. And these qualities give me great optimism about our species and optimism about our capacity, even at historically fraught moments like we, I think, are right now, give me hope and optimism that we can surpass those challenges.

Harlan Krumholz: How nice, we’re talking about the victory of light over dark in a week of Diwali, the Hindu festival that celebrates good over evil. Nicholas, you know how much I admire you. You really represent to me intellectual in academia, someone who thinks deeply about problems and then works to create public dialogue about them in highly constructive ways. Howie talked about your books. He also neglected to mention Death Foretold, I think, was maybe your first book, which gets to your background as a hospice doctor before you really fully invested as a professor of sociology and your roots in medicine.

I’ve been taken by all of your works and that they always give me much to reflect on. I wanted to direct the listeners to Blueprint, because I really felt that that was a masterpiece. And if anyone hasn’t had a chance to read it, it came out in 2019, and it really does combine a sort of deep exploration of literature, of the scientific literature with a humanism about who we are and where we’re going. I’ll just say that one of the main things that you did was you talked about the commonalities in societies and the ways in which if you look deeply, you see that we are set up to form societies and to form bonds and to need friendship and love. And I thought all of that was quite profound, and it really made me think.

I had written down, like you talked about the capacity to have and recognize individual identity, love for partners in offspring, friendship, social network, cooperation, preference for one’s own group, mild hierarchy that is relative to egalitarianism and social learning and teaching. I left that book thinking like, “We actually have the capacity to get along.” But you also talk quite a lot in the book about our propensity for tribalism and all of the negative things that have sometimes been emblematic of the human race.

How can we work to achieve the goodness? I mean, this is the problem, you see. And the United States, to me, is just a perfect example of what’s going on right now. Where you have seemingly irreconcilable forces that want simply to take advantage of each other at every turn and are tearing the nation apart. What can we do? I mean, what is the prescription here really to try to, in a way, nudge the society towards the better angels?

Nicholas Christakis: So actually “better angels” is of course a classic from Abraham Lincoln’s speech, and it was the title of Steve Pinker’s book. And if I can take a moment, I’d like to try to answer your question in a couple of ways. The first thing I’d like to say is that what I’m primarily concerned with is the great sweep of human evolution, so hundreds of thousands of years. How our evolutionary past has shaped us and endowed us with these wonderful qualities.

So for example, other animals sexually reproduce with each other, as we do, but we form sentimental attachments to the people that we’re having sex with. We love them. And this is unusual in the animal kingdom. Now, it’s actually not uncommon in birds. Most bird species form long-term attachments. We don’t think they have love for each other, just to be clear. But we’re not the only species that forms an attachment to its mates, but we do have that. And the human manifestation of it is love, which is extraordinary.

Other animals, of course, also, as I just said, reproduce with each other. But we do something else, which is we form long-term, non-reproductive unions with unrelated conspecifics with other members of our species. Namely, we have friends. This is extremely rare. This phenotype is very rare in the animal kingdom. We do it, certain other primates do it, whales, certain cetacean species do it, and elephants do it. Both Asian and African elephants have friendships. That’s pretty much it.

Those are the main examples. These social-living, intelligent, long-lived animals have friendships. So we are endowed with this capacity. Natural selection shaped this capacity. Incidentally, natural selection came up with this capacity for friendship independently in us and elephants. Our last common ancestor was 85 million years ago. And yet elephants have friends and we have friends.

This is a really interesting thing. The time horizon that I’m interested in is over let’s say three or four hundred thousand years that anatomically modern humans have been around is the forces that have shaped us on an evolutionary time. Now, the reason I think this is important is the following, because as you mentioned, we’re at a historically challenging moment. And Steve Pinker, in his book Better Angels of Our Nature, makes the compelling argument, which I agree with, that with the arrival of the Enlightenment in Europe and some of the philosophical advances during the 18th century, some of the philosophical advances that privileged the equality of human beings, the importance of sort of democratic governance—now, imperfectly applied, these were not applied, for example, initially to women, of course, we had slavery and colonialism—but philosophically this was an innovation, some of these ideas.

And simultaneous to that, the scientific advances which took place during the Enlightenment, the conquest of electricity and magnetism, the invention of the steam engine, all of these other technologies which took place, Steven Pinker argues that these philosophical advances in scientific advances redirected the trajectory of human experience. So that initially in Europe and then extending worldwide, we began to live longer, safer, more peaceful, and richer lives, that we were better off. And that human beings are becoming healthier and safer and more peaceful and so on, because of the action of historical forces.

But my argument is that we don’t need to rely just on these historical forces to make this argument. My argument is that deeper, more powerful, more ancient forces are at work compelling a good society. And in the book I kind of ape Martin Luther King, and I say, “The arc of our evolutionary history is long, but it bends towards goodness.” So I guess what I would say is is that there are historical fluctuations in how bad and awful we are, but the long arc of human evolutionary history is to endow us and to continue to endow us with these positive qualities. And I think we can use these qualities to address even the action of historical forces.

So right now we are facing a lot of divisions in our society. Of course, there’s climate change, there’s the Russian aggression in Ukraine, there’s what’s happening in Iran right now, there is the pandemic and the disagreements, between countries and within countries, how to deal with the worst pandemic we’ve had in a century. All of these are serious global problems. There’s rising inequality. But we can use some of these forces that we’ve been endowed with to try to counteract some of these problems to work together. And I can give you one illustration if you’re interested.

Harlan Krumholz: Yep, go ahead.

Nicholas Christakis: So one of the things you mentioned, Harlan, is that it’s almost a paradox that in order to be a social animal, we had to be endowed with the capacity to be individuals. In other words, natural selection equipped us with the ability to signal our unique identity and to recognize the unique identity of other people. Now in humans, we do this with our faces and they’re there for a purpose. And their purpose is to allow us to live socially.

Because if you want to make sure you remember who you had sex with or who was mean to you or nice to you, or who do you owe a favor to, for example, or you want to be able to signal to your mother, “This is me, not someone else’s offspring that you need to nurse,” and so on, you need the capacity to signal your individual identity. So this capacity for identity is crucial for living together. So that’s one thing that we have.

We also have, as you mentioned, as part of this suite of features, we have this in-group bias, which is we prefer to be nice to people that are in our group in comparison to other groups. Now, this is one of the more depressing realities of the human condition, but as part of that, we have this magnificent capacity to define those groups arbitrarily. For example, you can give those experiments that were done at Yale by Paul Bloom and his colleagues, you can give little infants like two year old toddlers, you randomly assign them to get different color T-shirts, and you give some toddlers yellow and some toddlers green.

They know that they didn’t do anything to deserve these T-shirts. You can test that they understand that it was random. And yet as soon as you give them these T-shirt colors, the green T-shirted kids say, “Oh, those yellow T-shirted kids, they are bad children. They should be punished. I want to give my toy to another kid with my colored T-shirt.” I mean it’s awful, but it’s arbitrary, the division that we make are arbitrary.

So now with this preamble, now let me give you how this is relevant to our current, what besets us now in American society. So we have a tremendous amount of division in our society right now, tremendous tribalism in our society. Where we’re divided along rich and poor and rural and urban and Republican and Democrat and Black and White. And you pick the divisions, there are atheists and religious people, and it goes on and on.

But we have two ways out of this dilemma. So one way out, so imagine a set of groups, you have a large population that is divided into a set of groups. One way out is to go up a level and to say, “Well, we’re all Americans, and these divisions that are arbitrary within us, let’s have a different division.” And this has been a part of our history for hundreds of years. Alexis de Tocqueville talked about the miraculous ability of Americans to take in, assimilate all these immigrant groups and redefine ourselves as American. And we have a shared identity as Americans. We don’t need to have these divisions within us.

You can exploit our groupiness and our capacity to define groups and go up a level and say, “We’re all Americans.” And in fact, I think that, very paradoxically—and this ability to go up a level is facilitated when we have a shared enemy like that trope in science fiction movies when the aliens invade and every nation on earth bands together to fight the aliens. I think that the collapse of the Soviet Union, when we had a common enemy, I think, we were more united. And I think one of the ironies of the collapse of the Soviet Union is I think it reverberated and fostered divisions within us because we didn’t have this shared adversary to the same extent anymore.

I’m not saying that’s the only reason, but that’s a factor. Okay, so one solution to our present dilemma is to go up a level. But there’s another solution and that’s to go down a level, down to the level of individuals. And this is the Martin Luther King solution, because remember what MLK says is that he looks forward to the time when his children will be judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character, as individuals. So my point is that these capacities for groupiness and for individuality that we are endowed with by evolution are tools we can use to actually address even the action of historical forces, such as the ones we are facing today.

Howard Forman: I’m going to pivot dramatically from that high-level view of society, but I want to go to something that you wrote in 2007, which was really a landmark paper on obesity. We just talked about obesity a couple of weeks ago with Dr. Ania Jastreboff, and we talked about treating obesity and the way we think about obesity. But you, 15 years ago, talked about obesity as something that is, in a simple way, contagious. Can you just talk briefly about that, and how that might inform the way we think about other types of learned behaviors or outcomes and so on?

Nicholas Christakis: Yeah, so I mean the basic idea is most people have the understanding that their choices and actions and behaviors are influenced by the choices and actions and behaviors of those around them. I mean, any parent raising children, you say, “Don’t hang out with the kids that are slackers. I want you to hang out with the kids that are studious, because that’ll help you be studious.” Or if your kids are hanging out with bank robbers, you’d be like, “I don’t want you hanging out with the bank robbers. I’d rather you hang out with someone who’s not a bank robber.” Because we all have this basic understanding, and this appreciation of the fact that we are influenced by others, person to person, is ancient.

But what’s become possible in the last 20 or 30 years is to really study these at a network level. In other words, to look at these so-called peer effects and see how they can spread hyperdyadically. Because, of course, if I influence you, my influence doesn’t stop there, because you then influence your friends and your friends’ friends influence their friends. So I can create the ripple effects in society such that when I take an action like I quit smoking, it may increase the probability that by 10% that each of my friends will quit smoking, and they in turn will increase the probability that their friends will quit smoking. If I quit smoking, I might create three other people that stop smoking, because of me, because I quit.

Now it’s very hard to prove this. And we started this work, as you suggested, we actually, that 2007 paper, we started working on it in 2001. It took six years to do that project, so it’s about 20 years ago now. We wanted to see whether we could find evidence for these social contagions that spread beyond pairs of individuals and that they would do so for things that weren’t necessarily obvious.

In other words, during the COVID pandemic, all of us had this intuitive understanding that the germ was spreading, and that even if you didn’t have COVID right now, and even if your friends didn’t have COVID, if your friends’ friends had COVID, they would infect your friends who would then infect you. So you had this notion of things spreading when it comes to germs, but not necessarily with other things like your body size or your voting behavior or your altruistic behavior, how kind you are to other people.

Many of these things which seem to be so deeply personal, in fact, can be shown, first using observational data and then ultimately using experiments, to depend on contagion effects. And so that’s what we did. We started with obesity, and we showed that your probability of gaining weight or losing weight depended very much on the probability of your friends, your friends’ friends, and your friends’ friends’ friends, of losing weight.

In 2010, we published our first experiments where we showed when we brought people into a lab and we randomly assigned them to play these altruistic games, so-called public goods games with strangers, and then a bell would ring and they’d interact with new strangers, and then a bell would ring and they’d interact with new strangers, we were able to show that if Tom is kind to Dick and Dick is kind to Harry and Harry’s kind to Sally, Sally will be kind to Jane. And so how Sally treats Jane depends on how Tom treated Dick, even though neither Sally or Jane ever saw or interacted with Tom or Dick.

And that’s because of these ripple effects. And we showed that in a laboratory setting that this was true, that “pay it forward” was real. And since then we’ve done all kinds of other experiments in Honduras, in Uganda, in India, we’ve worked around the world to show that you can go into developing world villages, shrewdly pick people who can have this type of structural influence, where they can start these kinds of social contagions, target them for a public health intervention like breastfeeding or vaccination or latrine usage or clean water interventions, and then watch the cascades spread through the village. So that we can change the behavior of a whole population just by targeting a small subset of people.

And I’ll say one more example. We just published a paper last month in the proceedings in National Academy [Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences] on a randomized trial we did among 2,500 women in 50 residential units in Mumbai. And we showed that we could get these women to use iron-fortified salt to reduce neonatal anemia and maternal anemia. So let’s say there are 400 women in this residential unit, we pick 10 women, and we teach them about iron-fortified salt. And before you know it, many other women who we didn’t even teach also start using iron-fortified salt. We can induce these social cascades. So that’s a bit about social contagion. I don’t know if I kind of meandered a little bit and I talked about a lot of different things, but…

Harlan Krumholz: No, I thought it was… I mean, look, that was a brilliant paper and I think it got people thinking about a lot of different ways that you can influence behaviors and that were influenced by those that are around us. And the use of Framingham as a first start for that paper, no one had thought to use a Framingham Heart study in a network analysis that might illuminate the influence of the people around you. It really continues to be a landmark study that has stimulated a ton of other work.

So what I want to tee up for you is what really surprised me is we are facing two existential, extrinsic risks to the race that maybe we fostered, but not purposely, climate change and the pandemic, viruses. And instead of leading the world to say, “We got to fight this together, and we’re facing the same threat,” that is, that would foster this sense of togetherness, it pushes our common humanity because as humans on this planet, we’re facing disease and we’re facing, actually, the potential that we’re going to have an uninhabitable sphere here, but it hasn’t done it. It’s become a tool, a political football, in order to basically try to advantage some over others. And it didn’t have that result. I mean, how do you interpret that? Why didn’t that stimulate the togetherness that we would all hope would happen?

Nicholas Christakis: I mean, on the pandemic front, this is also an old idea. There’s arguments by, there was a plague pandemic in Rome in the fifth century, and St. Cyprian talked about how we should all be united in fleshly equality. That in other words, this idea that when there’s this external threat that we should all be united is an ancient idea. People understand this idea that we should behave that way.

And we do sometimes and not always. So my point in telling these little vignettes about St. Cyprian is that this temptation to blame others is ancient, just as much as the sentiment that we shouldn’t be doing that, that we should be working together. And this partly relates to our tribalism that I mentioned earlier, which is in fact a depressing aspect of human nature. Because we unfortunately also have these dumb misguided tendencies as well, these awful tendencies.

And so I think it does require effort for us to band together. Now the good news is we have these tools. We have the tools to teach and learn from each other. We are endowed with a desire to cooperate. We are capable of cooperation. We are capable of friendship. We are capable of using these tools to work together to confront these dire threats. And I do agree with you, these are very serious threats. Now let’s not forget when all of us were in medical school, do you guys remember the nuclear countdown clock? That I don’t know what… Yeah. So everyone was really worried about nuclear war, which was a threat. We also had the HIV epidemic, which was a global pandemic.

We don’t talk about it as a global pandemic, but guys, as you guys know, it was a global pandemic and it killed and is still killing lots of people. So I want us to recognize that we have had these types of threats before. We did work together, both with a nuclear issue and the AIDS issue. Human beings were sloppy, but they were eventually able to work together. And I’m optimistic that we’ll do the same with climate change in the end. And I think partly that the young people will force this upon us. And I think as the changes become more and more apparent, as snow days disappear from New England, I think people will be incentivized.

Howard Forman: I want to say one last thing about you. I’ve never seen anyone write a better letter of recommendation than you. I’ve been fortunate to see at least a dozen of your letters—

Harlan Krumholz: Wait, a minute. What about mine?

Howard Forman: … over the years.

Harlan Krumholz: You haven’t seen my letters.

Howard Forman: No, I have seen yours. His are better.

Harlan Krumholz: Oh my God. I just like—

Howard Forman: Best letters I’ve ever seen. So you are—

Harlan Krumholz: I’m out of here.

Howard Forman: … an amazing mentor and a teacher.

Harlan Krumholz: Geez.

Howard Forman: And I personally appreciate you.

Harlan Krumholz: Oh, my God.

Howard Forman: So thanks for joining us on the Health & Veritas podcast.

Harlan Krumholz: Show me that letter. I want to see that letter.

Nicholas Christakis: It’s not about him, Howie, it’s about other students, as you, I think you know.

Harlan Krumholz: Well, that was great, Howie. I can listen to Nicholas forever. He really brings together so many different threads and has got so many different ideas. And really he’s emblematic of the very best at Yale, the very best of what an academic can be, full of ideas. And, anyway, I really enjoyed that. Let’s get to you now. So what’s on your mind this week?

Howard Forman: I wanted to just reflect on three things we talked about recently because they both all showed up in the news. I figure I’d give you three really quick updates. One, Leana Wen, who is a physician health policy leader, had a great opinion piece in The Washington Post Tuesday on concussions and young athletes. And as our listeners may recall, I raised this issue briefly at the end of an episode a few weeks ago, and I intend to come back to it again soon, because it’s a big topic and I think it’s under-covered.

But suffice it to say that this is a compelling read and makes a convincing argument that, one, we should abandon tackle football before high school, and, two, we need to follow the NFL lead by limiting tackling during practice. It’s hard to believe that our professional sports don’t do things that we allow our young athletes to do in high schools and youth leagues.

She further lets us know nearly 60% of concussions in high school football and nearly 70% of concussions in college football occur during practice: not during games, during practice. In the NFL, that number is 19%, and it’s down to 6% during the regular season. This is not me saying that government needs to regulate this. This is a plea to parents and those who supervise our children to use common sense to avoid long-term damage that is quite real and potentially devastating.

Second story I wanted to mention is in follow-up to your story last week when you talked about fluvoxamine. We now have a randomized double blind placebo controlled trial of ivermectin published in JAMA this week, demonstrating that there is no benefit to the use of ivermectin in mild to moderate COVID. It’s sad that we have to keep having more and more studies to convince people, but this study shows that hospitalizations and deaths were statistically the same in the two groups. It will not change the narrative that ivermectin can work in COVID, but there remains no reliable evidence of that.

And then lastly, I was really pleased to see an article by Gina Kolata in the New York Times science section this week summarizing the paper we discussed on disabilities in healthcare. For readers who may not wish to read the health affairs articles that we talked about, this piece summarized it really well. And this final line, quoting our friend and colleague who we’re going to have on the podcast soon, Dr. Tara Lagu, she says, “When it comes to discriminatory thinking about disability, ‘I know for sure that we have to change the culture of medicine.’” Which is a point that you had made, Harlan, when we discussed it last.

Harlan Krumholz: Oh, my gosh, chock full of information there, Howie. I just want to jump in on the one thing about the concussion. It’s not just football. There’s lots of talks about like, should we continue to have headers in soccer?

Howard Forman: Correct.

Harlan Krumholz: What’s the use of that?

Howard Forman: That’s right.

Harlan Krumholz: I think we need to be thinking broadly about areas where there may be brain injury that we just haven’t appreciated or thought about much yet—

Howard Forman: A hundred percent.

Harlan Krumholz: … can have long-term impact, and we ought to be paying a lot of…. We got to protect that cranium.

Howard Forman: I agree.

Harlan Krumholz: It’s just so—

Howard Forman: It’s too valuable.

Harlan Krumholz: … important. Anyway, I really appreciate all those points. They’re all good. They’re all very good. You’ve been listening to Health & Veritas with Harlan Krumholz and Howie Forman.

Howard Forman: So how did we do? To give us your feedback or keep the conversation going, you can find this on Twitter

Harlan Krumholz: I’m @hmkyale, that’s H-M-K Yale.

Howard Forman: And I’m @thehowie, that’s @T-H-E-H-O-W-I-E. You can also email us at health.veritas@yale.edu. Aside from Twitter and our podcast, I’m fortunate to be the faculty director of the healthcare track and founder of the MBA for Executives program at the Yale School of Management. Feel free to reach out via email for more information on our innovative programs, or you can check out our website at som.yale.edu/emba.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah, and we should give a shout out for Diwali, because there are so many of our colleagues who celebrate, and I love that holiday, it’s a victory of good over evil.

Howard Forman: It’s a happy holiday.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah, it’s a happy holiday.

Howard Forman: Yes.

Harlan Krumholz: Health & Veritas is produced with the Yale School of Management. Thanks to our researcher, Jenny Tan, and to our producer, Miranda Shafer. They are just terrific. Talk to you soon, Howie.

Howard Forman: Thanks very much, Harlan. Talk to you soon.