Newly identified fossil insect used 360-degree vision and sticky feet to find and snare its meals

CORVALLIS, Ore. – With bulging eyes, an elongated mouth and feet that oozed resin, a fossil insect identified by Oregon State University research is so different from anything alive today that it needed to be placed in its own, extinct family.

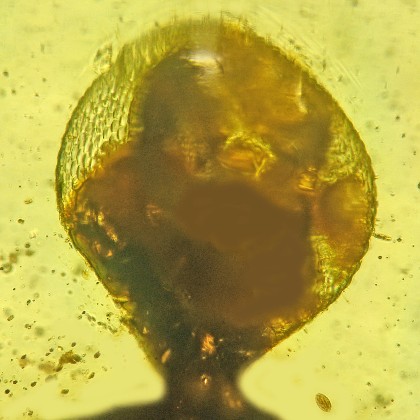

George Poinar Jr., professor emeritus in the OSU College of Science, named the insect Palaeotanyrhina exophthalma in a paper published in BioOne Complete. Encased in 100-million-year-old amber from Burma, P. exophthalma is a member of the Hemiptera order – a “true bug,” Poinar said.

“It is a small predator that used its protruding eyes to locate insect prey,” said Poinar, an international expert in using plant and animal life forms preserved in amber to learn about the biology and ecology of the distant past.

More than 80,000 species including cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, bed bugs and shield bugs comprise the order of Hemiptera, an ancient Greek word meaning half-winged. True bugs’ size varies widely, from as small as 1 millimeter to as large as 15 centimeters, but they all have a similar arrangement of sucking mouthparts.

P. exophthalma has a body length of just over 5 millimeters. It shares some features with members of the Reduvoidea superfamily, which includes the assassin bug and the kissing bug, but its long labium (lower mouth), its head shape and its forewing veins disqualify it from placement in any modern Reduvoidea family, Poinar said.

Thus he assigned it to a new, extinct family: Palaeotanyrhinidae.

“Its eyes provided a clear, 360-degree view of its habitat so it could see prey that might appear from any side,” Poinar said.

It reminded Poinar of the phrase, “Big brother is always watching you,” from George Orwell’s novel “1984” in which security cameras followed individuals’ every movement.

The other strange feature on this fossil is an extended sheath on the final leg segment of the front tarsus, he added.

“That sheath was filled with a resinous substance,” Poinar said. “The sticky substance was produced by dermal glands and helped the insect grasp potential prey.”

Péter Kóbor of the Plant Protection Institute at the Centre for Agricultural Research in Budapest collaborated on this research, as did Alex E. Brown of Berkeley, California.