The Brain’s Drainage System in 3 Dimensions

Meningeal lymphatic vessels are potential targets to treat brain diseases. Laboratories at Yale and the Paris Brain Institute (Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris) image brain drainage by meningeal lymphatics in mice and in humans.

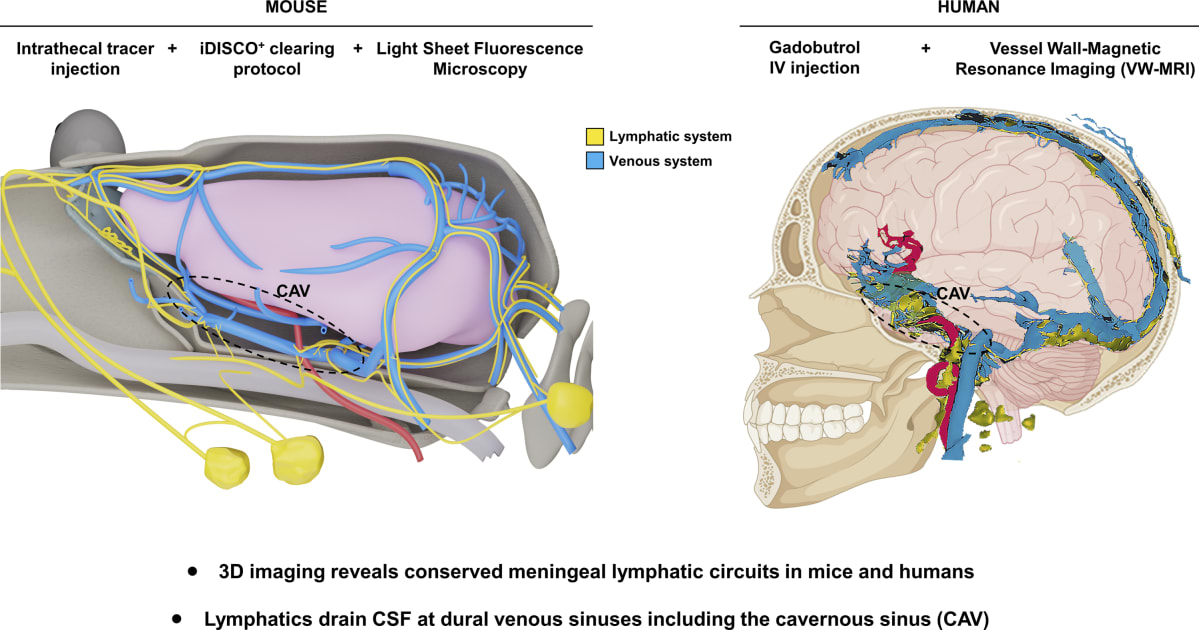

The recent Journal of Experimental Medicine paper led by Jean-Leon Thomas, PhD, professor of neurology, and Anne Eichmann, PhD, Ensign Professor of Medicine and professor of cellular and molecular physiology and co-director of Yale’s Cardiovascular Research Center (YCVRC), demonstrates that CSF drainage pathways are similar between mice and humans and reports a novel MRI-based imaging technique for patients with neurological diseases.

The lymphatic vascular system controls immune surveillance and waste elimination within tissues and organs. Lymphatic vessels are absent from the central nervous system (CNS) but present at the CNS borders, in the meninges that protect the brain and the spinal cord. The meningeal lymphatic vessels are draining into the lymph nodes of the neck and the peripheral immune system, which makes them key players in brain immunity control. The meningeal lymphatic vessels are also important for waste removal from the brain, by participating in the clearance of interstitial fluid and soluble proteins, as well as in the drainage of CSF that provides the brain with a protective fluid buffer against injury, a pathway for essential nutrients, and disposal system for cellular waste.

The meningeal lymphatic system affects neurological diseases in many mouse models, including Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, brain tumors and other conditions. “Because of its involvement in many diseases, the meningeal lymphatic system has attracted a lot of therapeutic interest” explains Laurent Jacob, PhD, first author of the study and a member of the Paris research team. “However, it remained unclear where the lymphatic recapture of CSF molecules occurs in the context of the whole head, in mice or in humans.”

To learn more about the architecture and function of the meningeal lymphatic network, the team investigated CSF lymphatic drainage using postmortem light-sheet imaging in mice and real-time magnetic resonance imaging in humans. By combining these approaches, the authors rebuilt the entire lymphatic drainage network of the CSF.

The 3D imaging showed that the meningeal lymphatics contact the venous sinuses of the dura mater, and revealed an extensive meningeal lymphatic network around the cavernous sinus in the anterior part of the skull. From there, meningeal lymphatics exit the skull through cranial foramina and drain into cervical lymph nodes.

Stéphanie Lenck, MD, also at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, performed quantitative lymphatic MRI in 11 patients affected by various neurological diseases. She established a procedure for 3D-visualization of all blood and lymphatic vasculature in the meninges and the neck that revealed a significantly greater meningeal lymphatic volume in men than in women. Future research will have to explore whether this anatomical data is causally related to the greater predisposition of women to develop neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis, meningiomas or intracranial hypertension.

“Meningeal lymphatic vessels are potential targets to treat brain diseases,” said Eichmann. “Laboratories at Yale are making progress toward elucidating their function by imaging brain drainage by meningeal lymphatics in mice and in humans.”

The study was funded by the European Research Council (ERC), the French National Research Agency (ANR), and the Paris Brain Institute (ICM).